The word “health” conjures everyday personal decisions — what we eat, how much we exercise or sleep or how often we go to the doctor — things that appear to be under our control. But instead of looking at what we choose to eat, what if we put the onus on the types of foods we have access to and the quality of the foods we can afford? Instead of looking at how much we exercise or sleep, what if we examined how many and what kinds of jobs we work, how much they pay us and the impact this has on our quality of life? Instead of looking at how often we go to the doctor, what if we paid closer attention to who has insurance and the quality of the care we receive?

This pivot in framing causes the conversation to shift — from one that centers around our own individual behaviors, to one that highlights the collective behaviors of communities and the systems they support. These are known as “Social Determinants of Health” — an increasingly vital body of international study that examines the conditions that surround and shape us, conditions that, when looked at honestly, are seen to produce highly inequitable and unfair realities.

These inequities have long been here — much of Charlottesville and its surrounding counties were literally built on them. But as the COVID-19 pandemic has swept through our communities, we’ve seen them heightened and exacerbated as never before on unparalleled levels.

Inequalities in health status in the U.S. are large, persistent and increasing. Research documents that poverty, income and wealth inequality, poor quality of life, racism, sex discrimination and low socioeconomic conditions are the major risk factors for ill health and health inequalities … conditions such as polluted environments, inadequate housing, absence of mass transportation, lack of educational and employment opportunities and unsafe working conditions are implicated in producing inequitable health outcomes. These systematic, avoidable disadvantages are interconnected, cumulative, intergenerational and associated with lower capacity for full participation in society. … Great social costs arise from these inequities, including threats to economic development, democracy and the social health of the nation.

Our health district consists of about 250,000 people in Charlottesville and the counties of Albemarle, Fluvanna, Greene, Louisa and Nelson. African Americans make up 13.7% of that — or 34,186 people — while White residents make up 81.5% — or 203,372 people.

If the COVID-19 cases were equally distributed, out of the 325 total people who have tested positive so far, 44 would be African American and 264 would be white. But in actuality, 99 African Americans have tested positive — representing 30.4% of the total cases, or more than two times the proportional rate — along with 193 white people, representing about 59.3%. This points directly back to the broken and inequitable state of our Social Determinants of Health.

The rate of African American hospitalizations due to COVID-19 is even higher, at nearly four times the proportional rate. Currently 23 white people, or about 37.7%, have been hospitalized, alongside 32 Black people, or about 52.5%. If the systems were equitable, however, 49 white people would have been hospitalized, and just eight Black residents would have been hospitalized.

These racial inequities are occurring all across the country — in Richmond, where African Americans make up 47.8% of the population, they have at least 73.5% of the positive cases. And though our health system is perhaps the most obvious place to look in the midst of a global health pandemic, in fact all of our systems are broadcasting sweeping injustices, proving just how interconnected one’s job is to one’s food, and one’s kids are with one’s sense of social inclusivity, and one’s trauma is with one’s physical health. Now imagine if these were all under siege at once, and in fact, had been for generations.

CIM used these Social Determinants of Health as our foundational framework and guideposts to bring you stories of how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted some of our African American communities.

A key structural construct of our ecosystem is that we’re prevented from experiencing each other’s hardships. The pandemic has brought lots of talk and acts of “togetherness,” and yet, as we see now more than ever, our communities are also filled with injustices that often occur in segregated and isolating realities. With this series, we aim to bring you detailed accounts of these long-standing and interconnected systems and the stories of community members waging daily battles, on micro and macro levels, to change and overthrow them.

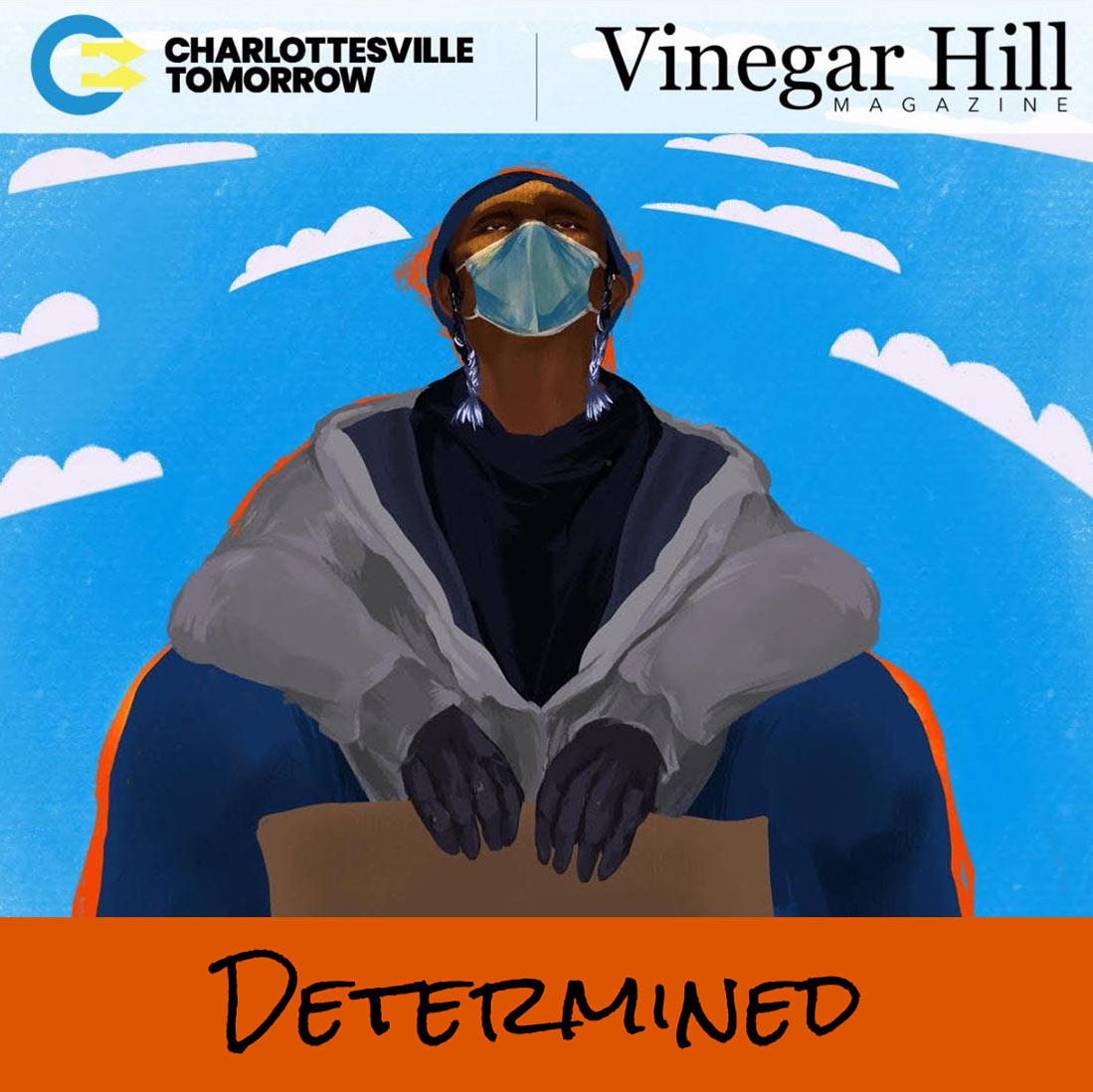

Determined: Stories of resilience in a broken ecosystem series published jointly on Vinegar Hill Magazine’s website and print edition and Charlottesville Tomorrow’s website in May and June of 2021.

Reporting by Jordy Yager

Original series artwork by Sahara Clemons: https://www.cvilletomorrow.org/articles/about-the-artist

Additional funding provided by the Facebook Journalism Project’s COVID-19 Local News Relief Fund Grant Program.

View the Determined series at Vinegar Hill Magazine

View the Determined series at Charlottesville Tomorrow